How Quest Sought the Truth

Ivana Brlić-Mažuranić

I

ONCE upon a time very long ago there lived an old man in a glade in the midst of an ancient forest. His name was Witting, and he lived there with his three grandsons. Now this old man was all alone in the world save for these three grandsons, and he had been father and mother to them from the time when they were quite little. But now they were full-grown lads, so tall that they came up to their grandfather's shoulder, and even taller. Their names were Bluster, Careful and Quest.

One spring morning old Witting got up early, before the sun had risen, called his three grandsons and told them to go into the wood where they had gathered honey last year; to see how the Httle bees had come through the winter, and whether they had waked up yet from their winter sleep. Careful, Bluster and Quest got up, dressed, and went out.

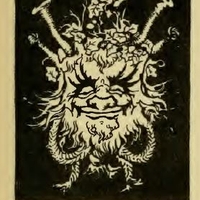

It was a good way to the place where the bees lived. Now all three brothers knew every pathway in the woods, and so they strode cheerily and boldly along through the great forest. All the same it was somewhat dark and eerie under the trees, for the sun was not yet up and neither bird nor beast stirring. Presently the lads began to feel a little scared in that great silence, because just at dawn, before sunrise, the wicked Rampogusto, King of Forest Goblins, loves to range the forest, gliding softy from tree to tree in the gloom.

So the brothers started to ask one another about all the wonderful things there might be in the world. But as not one of them had ever been outside the forest, none could tell the others anything about the world; and so they only became more and more depressed. At last, to keep up their courage a bit, they began to sing and call upon All-Rosy to bring out the Sun:

Little lord All-Rosy bright,

Bring golden Sun to give us light;

Show thyself, All-Rosy bright,

Loora-la, Loora-la lay!

Singing at the top of their voices, the lads walked through the woods towards a spot from where they could see a second range of mountains. As they neared the spot they saw a light above those mountains brighter than they had ever seen before, and it fluttered like a golden banner.

The lads were dumbfounded with amazement, when all of a sudden the light vanished from off the mountain and reappeared above a great rock nearer at hand, then still nearer, above an old lime-tree, and at last shone like burnished gold right in front of them. And then they saw that it was a lovely youth in glittering raiment, and that it was his golden cloak which fluttered Uke a golden banner. They could not bear to look upon the face of the youth, but covered their eyes with their hands for very fear. Why do you call me, if you are afraid of me, you silly fellows?” laughed the golden youth —for he was All-Rosy. “You call on All-Rosy, and then you are afraid of All-Rosy. You talk about the wide world, but you do not know the wide world. Come along with me and I will show you the world, both earth and heaven, and tell you what is in store for you.”

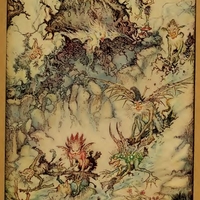

Thus spoke All-Rosy, and twirled his golden cloak so that he caught up Bluster, Careful and Quest, all three in its shimmering folds. Round went All-Rosy and round went the cloak, and the brothers, clinging to the hem of the cloak, spun round with it, round and round and round again, and all the world passed before their eyes. First they saw all the treasure and all the lands and all the possessions and the riches that were then in the world. And they went on whirling round and round and round again, and saw all the armies, and all spears and all arrows and all the captains and all plunder which were then in the world. And the cloak twirled yet more quickly, round and round and round again, and all of a sudden they saw all the stars, great and small, and the moon and the Seven Sisters and the winds and all the clouds. The brothers were quite dazed with so many sights, and still the cloak went on twirling and whirling with a rustling, rushing sound like a golden banner. At last the golden hem fluttered down; and Bluster, Careful and Quest stood once more on the turf. Before them stood the golden youth All-Rosy as before, and said to them:

“There, my lads, now you have seen all there is to see in the world. Listen to what is in store for you and what you must do to be lucky.”

At that the brothers became more scared than ever, yet they pricked up their ears and paid good heed, so as to remember everything very carefully. But All-Rosy went on at once:

“There! this is what you must do. Stay in the glade, and don't leave your grandfather until he leaves you; and do not go into the world, neither for good nor for evil, until you have repaid your grandfather for all his love to you.” And as All-Rosy said this, he twirled his cloak round and vanished, as though he had never been; and lo, it was day in the forest.

But Rampogusto, King of the Forest Goblins, had seen and heard everything. Like a wraith of mist he had slipped from tree to tree and kept himself hidden from the brothers among the branches of an old beech-tree.

Rampogusto had always hated old Witting. He hated him as a mean scoundrel hates an upright man, and above all things he hated him because the old man had, brought the sacred fire to the glade so that it might never go out, and the smoke of that fire made Rampogusto cough most horribly.

So Rampogusto wasn't pleased with the idea that the brothers should obey All-Rosy, and stay beside their grandfather and look after him; but he bethought himself how he could harm old Witting, and somehow turn his grandsons against him.

Therefore, no sooner had Bluster, Careful and Quest recovered from their amazement and turned to go home than Rampogusto slipped swiftly, like a cloud before the wind, to a wooded glen where there was a big osier clump, which was chock-full of goblins—tiny, ugly, humpy, grubby, boss-eyed, and what not, all playing about like mad creatures. They squeaked and they squawked, they jumped and they romped; they were a pack of harum-scarum imps, no good to anybody and no harm either, so long as a man did not take them into his company. But Rampogusto knew how to manage that.

So he picked out three of them, and told them to jump each on one of the brothers, and see how they might harm old Witting through his grandsons.

Now while Rampogusto was busy choosing his goblins. Bluster, Careful and Quest went on their way; and so scared were they that they clean forgot all they had seen during their flight and everything that All-Rosy had told them.

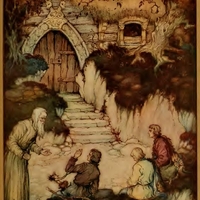

So they came back to the cabin, and sat down on a stone outside and told their grandfather what had happened to them.

“And what did you see as you were flying round, and what did AU-Rosy tell you?” Witting asked Careful, his eldest grandson. Now Careful was in a real fix, because he had clean forgotten, neither could he remember what All-Rosy had told him. But from under the stone where they were sitting crept a wee hobgoblin—ugly and homed and grey as a mouse.

The goblin tweaked Careful's shirt from behind and whispered: “Say: I have seen great riches, hundreds of beehives, a house of carved wood and heaps of fine furs. And All-Rosy said to me: 'Thou shalt be the richest of all the three brothers.”

Careful never bothered to think whether this was the truth that the imp was suggesting, but just turned and repeated it word for word to his grandfather. No sooner had he spoken than the goblin hopped into his pouch, curled himself up in a comer of the pouch—and there stopped!

Then Witting asked Bluster, the second grandson, what he might have seen in his flight, and what All-Rosy might have told him? And Bluster, too, had noticed nothing and remembered nothing. But from under the stone crept the second hobgoblin, quite small, ill-favoured, horned and smutty as a polecat. The goblin plucked Bluster by the shirt and whispered: “Say: I saw lots of armed men, many bows and arrows and slaves galore in chains. And All-Rosy said to me: 'Thou shalt be the mightiest of the brothers.”

Bluster considered no more than Careful had done, but was very pleased, and lied to his grandfather even as the goblin had prompted him. And the goblin at once jumped on his neck and crawled down his shirt, hid in his bosom, and stopped there.

Now the grandfather asked the youngest grandson. Quest, but he, too, could recall nothing. And from under the stone crept the third hobgoblin, the youngest, the ugliest, homed with big horns, and black as a mole. The hobgoblin tugged Quest by the shirt and whispered: “Say: I have seen all the heavens and all the stars and all clouds. And All-Rosy said to me: 'Thou shalt be the wisest among men and know what the winds say and the stars tell.”

But Quest loved the truth, and so he would not listen to the goblin nor lie to his grandfather, but kicked the goblin and said to his grandfather: “I don't know, grandfather, what I saw or what I heard.”

The goblin gave a squeal, bit Quest's foot, and then scuttled away under the stone like a lizard. But Quest gathered potent herbs and bound up his foot with them, so that it might heal quickly.

II

Now the goblin whom Quest had kicked first scooted away under the stone, and then wriggled into the grass, and hopped off through the grass into the woods, and through the woods into the osier clump.

He went up to Rampogusto all shaking with fright and said: “Rampogusto, dread sovereign, I wasn't able to jump on that youth whom you gave into my care.”

Then Rampogusto fell into a frightful rage, because he knew those three brothers well, and most of all he feared Quest, lest he should remember the truth. For if Quest were to remember the truth, why, then Rampogusto would never be able to get rid of old Witting nor the sacred fire.

So he seized the little goblin by the horns, picked him up and dusted him soundly with a big birch-rod.

“Go back!” he roared—“go back to the young man, and it will be a black day for you if ever he remembers the truth!”

With these words Rampogusto let the goblin go; and the goblin, scared half out of his wits, squatted for three days in the osier clump and considered and considered how he might fulfil his difficult task. “I shall have as much trouble with Quest, for sure, as Quest with me,” reflected the goblin. For he was a scatter-brained little silly, and did not care at all for a tiresome job.

But while he squatted in the osier clump those other two imps were already at work, the one in Careful's pouch and the other in Bluster's bosom. From that day forth Careful and Bluster began to rove over hill and dale, and even slept but little at home—and all because of the goblins! There was the goblin curled up in the bottom of Careful's pouch, and that goblin loved riches better than the horn over his right eye.

So all day long he butted Careful in the ribs, teasing and goading him on: “Hurry up, get on! We must seek, we must find! Let's look for bees, let's gather honey, and then we will keep a tally with rows and rows of scores!”

So said the goblin, because in those days they reckoned up a man's possessions with tallies.

Now a tally is only a long wooden stick with a notch cut in it for every sum that is owing to a man!

But Bluster's goblin butted him in the breast, and that goblin wanted to be the strongest of all and lord of all the earth. So he worried and worried Bluster, and urged him to roam through the woods looking for young ash plants and slender maple saplings to make a warrior's outfit and weapons. “Hurry up, get on!” teased the goblin. „You must seek, you must find! Spears, bows and arrows to suit a hero's mind, so that man and beast may tremble before us.”

And both Bluster and Careful listened to their goblins, and went off after their own concerns as the goblins led them.

But Quest stayed with his grandfather that day and yet other three days, and all the time he puzzled and puzzled over whatever it was that All-Rosy might have told him; because Quest wanted to tell his grandfather the truth ; but, alas ! he could not remember it at all!

So that day went by, and the next, and so three days; and on the third day Quest said to his grandfather:

„Good-bye, grandfather. I am going to the hills, and shall not come back until I remember the truth, if it should take me ten years.”

Now Witting's hair was grey, and there was little he cared for in this world except his grandson Quest, and him he loved and cherished as a withered leaf cherishes a drop of dew. So the old man started sadly and said:

“What good will the truth be to me, my boy, when I may be dead and gone long before you remember it?”

This he said, and in his heart he grieved far more even than he showed in his words ; and he thought: How could the boy leave me!” But Quest replied:

“I must go, grandfather, because I have thought it out, and that seems the right thing to me.”

Witting was a wise old man, and considered: “Perhaps there is more wisdom in a young head than in an old one; only if the poor lad is doing wrong it's a sad weird he will have to dree—because he is so gentle and upright.” And as Witting thought of that he grew sadder than ever, but said nothing more. He just kissed his grandson good-bye and bade him go where he wished.

But Quest's heart sadly misgave him because of his grandfather, and he very, very nearly changed his mind on the threshold and stayed beside him. But he forced himself to do as he had made up his mind to, and went out and away into the hills.

Just as Quest parted from his grandfather his imp thought he might as well get out of the osier clump and tackle that tiresome job; and he reached the clearing just as Quest was hurrying away.

So Quest went off to the hills, very downcast and sad; and when he came to the first rock, lo and behold, there was the goblin, gibbering.

“Why”, thought Quest, “it's the very same one—quite small, misshapen, black as a mole and with big horns.”

The goblin stood right in Quest's way, and would not let him pass. So Quest got angry with the little monster for hindering him like this; he picked up a stone, threw it at the goblin, and hit him squarely between the horns. “Now I've killed him,” thought Quest.

“Well, evidently stones won't drive him off,” said Quest. So he went round the goblin and forward on his way. But the imp scuttled on in front of him, to the right and to the left, and then straight in front, for all the world like a rabbit.

At last they came to a little level spot between cliffs—a very stony place; and on one side of it there was a deep well-spring. “Here will I stay,” said Quest; and he at once spread out his sheepskin coat under a crab-tree and sat down, so that he might reflect in peace and remember what All-Rosy had verily and truly told him.

But when the imp saw that, he squatted down straight in front of Quest under the tree, played silly tricks on him, and worried him horribly. He chased lizards under Quest's feet, threw burrs at his shirt, and slipped grasshoppers up his sleeves.

“Oh dear, this is most annoying!” thought Quest, when it had gone on for some little time. “I have left my wise old grandfather, my brothers and my home, so that I might be in quiet and remember the truth—and here am I wasting my time with this homed imp of mischief!”

But as he had come out in a good cause, he nevertheless thought it the right thing to stay where he was.

III

So Quest and the goblin lived together on that lone ledge between the cliffs, and each day was like the first. The goblin worried Quest so that he couldn't get on with his thinking.

On a clear morning Quest would rise from sleep and feel happy. “How still it is, how lovely! Surely to-day I shall remember the truth!” And lo, from the branch overhead a handful of crabs would come tumbling about his ears, so that his head buzzed and his thoughts all got mixed. And there was the little monster mocking him from the crab-tree and laughing fit to burst. Or Quest would be lying in the shade, thinking most beautifully, till he felt like saying: “There, there now, now it will come back to me, now I shall puzzle out the truth!” And then the goblin would squirt him all over with ice-cold water from the spring through a hollow elder twig—and again Quest would clean forget what he had already thought out.

There was no silly trick nor idle joke that the goblin did not play on Quest on the ledge there. And yet all might have been well, if Quest hadn't found it just a tiny bit amusing to watch these tomfooleries; and though he was thinking hard about his task, yet his eyes would wander and look round to see what the imp might be doing next.

Quest was angry with himself over this, because he was wearying more and more for his grandfather, and he saw full well that he would never remember the truth while the goblin was about.

“I must get rid of him,” said Quest.

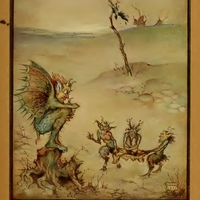

Well, one fine morning the goblin invented a new game. He climbed up the cliff where there was a steep water-course in the face of the rock, got astride a smooth bit of wood as if it had been a hobby-horse, and then scooted down the watercourse like a streak of lightning! This prank pleased the little wretch so mightily that he must needs have company to enjoy it the better! So he whistled on a blade of grass till it rang over hill and dale, and lo, from scrub and rock and osier clump the goblins came scuttling along, all tiny like himself. He gave orders, and every man-jack of them took a stick and shinned up the cliff with it. My word! how they got astride their hobbyhorses and hurtled down the water-course! There were all sorts and sizes and kinds of goblins—red as a robin's breast, green as greenfinches, woolly as lambs, naked as frogs, homed as snails, bald as mice. They careered down the water-course like a crazy company on crazy horses. Down they flew, each close at the other's heels, never stopping till they came to the middle of the ledge; and there was a great stone all overgrown with moss. There they were brought up short, and what with the bump of stopping so suddenly and sheer high spirits they tumbled and scrambled about all atop of one another in the moss!

Shrieking with glee, the silly crew had made the trip some two or three times already, and poor Quest was hard put to it between two thoughts. For one thing, he wanted to watch the imps and be amused by them, and for another he was angry with them for making such a hullabaloo that he could not remember the truth. So he shilly-shallied awhile, and at last he said: “Well, this is past a joke. I must get rid of these good-for-nothing loons, because while they are here I might as well have stopped at home.”

And as Quest considered the matter, he noticed that as they rushed down the water-course they made straight for the spring, and that, but for the big stone, they would all have toppled into it head foremost. So Quest crouched behind the stone, and when the imps came dashing down again guffawing and chuckling as before, he quickly rolled the stone aside, and the whole mad party rushed straight on to the well-spring—right on to it and then into it, head first, each on top of the other—red as robin's breasts, green as greenfinches, woolly as lambs, naked as frogs, homed as snails, bald-headed as mice — and first of all the one who had fastened himself on to Quest. . . .

And then Quest tipped a big flat stone over the well, and all the goblins were caught inside like flies in a pitcher. Quest was ever so pleased to have got rid of the goblins, sat down and made sure he would now recollect the truth in good earnest.

But he had no luck, because down in the well the goblins began to wriggle and to ramp as never before. Through every gap and chink shot up tiny flames which the goblins gave out in their fright and distress. The flames danced and wavered round the spring till Quest's head was all in a whirl. He closed his eyes, so that their flashing should not make him giddy.

But then there arose from the pit such a noise, hubbub, knocking and banging, barking and yowling, such yelling and shrieking for help, that Quest's ears were like to burst; and how could he even try to think through it? He stopped his ears so as not to hear.

Then a smell of brimstone and sulphur drifted over to him. Through every crack and crevice oozed thick sooty smoke which the imps belched forth in their extremity. Smoke and sulphur fumes writhed round Quest; they choked and smothered him.

So Quest saw there was no help for it. “Goblins shut up,” said he, “are a hundred times worse than goblins at large. So I'll just go and let them out, since I can't get rid of them anyhow. After all, I am better off with their tomfooleries than with all that yammering.”

So he went and lifted off the stone; and the terrified goblins scuttled away in all directions like so many wild cats, and ran away into the woods and never came back to the ledge any more.

None stayed behind, but only the one black as a mole and with big horns, because he did not dare to leave Quest for fear of Rampogusto.

But even he sobered down a little from that day forward, and had more respect for Quest than before.

And so these two came to a sort of arrangement between them; they got used to one another and Hved side by side on the stony ledge.

In that way close on to a year slipped by, and Quest was no nearer remembering what All-Rosy had really truly told him.

When the year was almost gone the goblin began to be most horribly bored. “How much longer have I got to stick here?” thought he. So one evening, just as Quest was about to fall asleep, the imp wriggled up to him and said:

“Well, my friend, here you've been sitting for close on a year and a day, and what's the good of it? Who knows but perhaps in the meantime your old grand-dad has died all alone in his cabin.”

A pang shot through Quest's heart as if he had been struck with a knife, but he said: “There, I have made up my mind not to budge from here until I remember the truth, because truth comes before all things.” Thus said Quest, because he was upright and of good parts.

But all the same he was deeply troubled by what the goblin had said about his grandfather. He never slept a wink all night, but racked his brains and thought: “How is it with the old man, my dear grandfather?”

IV

Now all this time the grandfather went on living with Careful and Bluster in the glade—only life had taken a very sad turn for the old man. His grandsons ceased to trouble about him, nor would they stay near him. They bade him neither “Goodmorning” nor “Good-night,” and only went about their own affairs and listened to the goblins they harboured, the one in his pouch and the other in his bosom.

Every day Careful brought more bees from the forest, felled timber, shaped rafters, and gradually built a new cabin. He carved himself ten tallies, and every day he counted and reckoned over and over again when these tallies would be filled up.

As for Bluster, he went hunting and reiving, bringing home game and furs, plunder and treasure; and one day he even brought along two slaves whom he had taken, so that they might work for the brothers and wait upon them.

All this was very hard and disagreeable for the old man, and harder and more disagreeable still were the looks he got from his grandsons. What use had they for an old man who would not be served by the slaves, but disgraced his grandsons by cutting wood and drawing water from the well for himself? At last there wasn't a thing about the old man that didn’t annoy his grandsons, even this, that every day he would put a log on the sacred fire.

Old Witting saw very well whither all this would lead, and that very soon they would be thinking of getting rid of him altogether. He did not care so much about his life, because life was not much use to him, but he was sorry to die before seeing Quest once more, the dear lad who was the joy of his old age.

One evening—and it was the very evening when Quest was so troubled in his mind thinking of his grandfather—Careful said to Bluster: “Come along, brother, let's get rid of grandfather. You have weapons. Wait for him by the well and kill him.”

Now Careful said this because he specially wanted the old cabin at all costs, so as to put up beehives on that spot. “I can't,” replied Bluster, whose heart had not grown so hard, amidst bloodshed and robbery, as Careful's among his riches and his tallies.

But Careful would not give over, because the imp in his bag went on whispering and nagging. The imp in his pouch knew very well that Careful would be the first to put the old man away, and so gain him great credit with Rampogusto.

Careful tried hard to talk over Bluster, but Bluster could not bring himself to kill his grandfather with his own hand. So at last they agreed and arranged that they would that very night bum down the old man's hut—bum it down with the old man inside!

When all was quiet in the glade, they sent out the slaves to watch the traps in the woods that night. But the brothers crept up softly to Witting's cabin, shut the outer door tight with a thick wedge, so that the old man might not escape from the flames, and then set fire to the four comers of the house. . . .

When all was done they went away and away into the hills so as not to hear their poor old grandfather crying out for help. They made up their minds to go over the whole of the mountain as far as they could, and not to come back until next day, when all would be over, and their grandfather and the cabin would be burnt up together.

So they went, and the flames began to lick upwards slowly round the comers. But the rafters were of seasoned walnut, hard as stone, and though the fire licked and crept all round them it could not catch properly, and so it was late at night before the flames took hold of the roof.

Old Witting awoke, opened his eyes and saw that the roof was ablaze over his head. He got up and went to the door, and when he found that it was fastened with a heavy wedge he knew at once whose doing it was.

“Oh, my children! my poor darlings!” said the old man, “you have taken from your hearts to add to your wretched talHes; and behold, your tallies are not even full, and there are many notches still lacking; but your hearts are empty to the bottom already, since you could burn your own grandfather and the cabin where you were born.”

That was all the thought that Father Witting gave to Careful and Bluster. After that he thought neither good nor bad about them, nor did he grieve over them further, but went and sat down quietly to wait for death.

He sat on the oak chest and meditated upon his long life; and whatever there had been in it, there was nothing he was sorry for save only this, that Quest was not with him in his last hour—Quest, his darling child, for whom he had grieved so much.

So he sat still, while the roof was already blazing away like a torch.

The rafters burned and burned, the ceiling began to crack. It blazed, cracked, then gave way on either side of the old man, and rafters and ceiling crashed down amid the flames into the cabin. The flames billowed round Witting, the roof gaped above his head. Already he saw the dawn pale in the sky before sunrise. Old Witting rose to his feet, raised his hands to heaven, and so waited for the flames to carry him away from this world, the old man and his old homestead together.

V

Quest worried terribly that night, and when morning broke he went to the spring to cool his burning face.

The sun was just up in the sky when Questreached the spring, and when he came there he saw a light shining in the water. It shone, it rose, and lo! beside the spring and before Quest stood a lovely youth in golden raiment. It was All-Rosy.

Quest started with joy, and said: “My little lord All-Rosy bright, how I have longed for you! Do tell me what you told me then that I must do? Here I have been racking my brains and tormenting myself and calling on all my wits for a year and a day—and I cannot remember the truth!”

As Quest said this, All-Rosy rather crossly shook his head and his golden curls.

“Eh, boy, boy! I told you to stay with your grandfather till you had rendered him the love you owe him, and not to leave him till he left you,” said All-Rosy.

And then he went on: “I thought you were wiser than your brothers, and there you are the most foolish of the three. Here you have been racking your brains and calling on your wits to help you for a year and a day so that you might remember the truth; and if you had listened to your heart when it told you on the threshold of your cabin to turn back and not to leave your old grandfather—why then, you silly boy, you would have had the truth, even without wits!”

Thus spoke All-Rosy. Once more he crossly shook his head with the golden curls; then he took his golden cloak about him and vanished.

Shamed and troubled, Quest remained alone beside the spring, and from between the stones he heard the imp giggling—the hobgoblin, quite small, misshapen, and homed with big horns. The little wretch was pleased because All-Rosy had shamed Quest, who always gave himself such righteous airs; but when Quest roused himself from his first amazement he called out joyfully:

“Now I'll just wash quickly and then fly to my dear old grandfather.” This he said and knelt by the spring to wash. Quest leaned down to reach the water, leaned down too far, lost his balance, and fell into the spring.

Fell into the spring and was drowned. . . .

VI

THE hobgoblin jumped up from among the stones, leaped to the edge of the spring, and looked down to see with his own eyes whether it was really true.

Yes, Quest was really truly drowned. There he lay at the bottom of the water, white as wax.

“Yoho, yoho, yo hey!” yelled the goblin, who was only a poor silly. “Yoho, yoho, yo hey! my friend, we're off to-day!”

The imp yelled so that all the rocks round the ledge rang with the noise. Then he heaved up the stone that lay by the edge of the spring, and the stone toppled over and covered the spring like a lid. Next the imp flung Quest's skin-coat on the top of the stone; last of all he went and sat on the coat, and then he began to skip and to frolic.

“Yoho, yoho! my job is done!” yelled the goblin.

But it wasn't for long that he skipped on the skin; it wasn't for long that he yelled.

For when the goblin had tired himself out, he looked round the ledge, and a queer feeling came over him.

You see, the goblin had got used to Quest. Never before had he had such an easy time as with that good youth. He had been allowed to fool about as he chose, without anybody scolding him or telling him to stop; and now that he came to think of it, he would have to go back to the osier clump, to the mire, to his angry King Rampogusto, and go on repeating the old goblin chatter among five hundred other goblins—all of them just as he used to be himself.

He had lost the habit of it. He began to think– to think a very little. He began to feel sad–just a little sad, then more and more miserable; and at last he was wringing and beating his hands, and the silly, thoughtless goblin, who a minute ago had been yelling with glee, was now weeping and wailing with grief and rolling about on the coat all crazy with distress.

He wept and he howled till all his former yelling was clean nothing in comparison. For a goblin is always a goblin. Once he starts wailing he wails with a vengeance. And he pulled the fur out of the skin-coat in handfuls, and rolled about on it as if he had taken leave of his senses.

Now just at that moment Bluster and Careful came to the lone ledge.

They had wandered all over the mountain, and were now on their way home to the glade to see if their grandfather and the cabin were quite burnt up. On the way back they came to a lone ledge where they had never been before.

Bluster and Careful heard something wailing, and caught sight of Quest's skin-coat; and they thought at once that Quest must have come to grief somehow.

Not that they felt sorry for their brother because they could not grieve for anybody while the goblins were about them.

But at that moment their goblins began to wriggle, because they could hear that one of their own kind was in trouble. Now there is no sort that sticks more closely together and none more faithful in trouble than the hobgoblins were. In the osier clump they would fight and squabble all day; but if there was trouble each would give the skin off his shins for the other!

So they wriggled and they worried; they pricked up their ears, and then peered out, the one from the pouch and the other from the shirt. And as they peered they at once saw a brother of theirs rolling about with somebody or something—rolling and writhing, and nothing to be seen but the fur flying.

“A wild beast is worrying him!” cried the terrified goblins. They jumped out, one out of Careful's pouch and the other out of Bluster's bosom, and scuttled off to help their friend.

But when they reached him, he would still do nothing but roll about on the skin and howl:

“The boy is dead!—the boy is dead!” The other two goblins tried to quiet him, and thought: “Maybe a thorn has got into his paw, or a midge into his ear”—because they had never lived with a righteous man, and did not know what it means to lament for others.

But the first goblin went on wailing so that you couldn't hear yourself speak, and he wouldn't be comforted either.

So the other goblins were in a fine taking as to what they were to do with him? Nor could they leave him there in his sore trouble. At last they had an idea. Each laid hold of the sheep-skin coat by one sleeve, and so they dragged along the coat with their brother inside, scuttled away into the woods, and out of the woods into the osier clump and home to Rampogusto.

So for the first time for a year and a day Bluster and Careful were quit of their goblins. When the imps hopped away from them, the brothers felt as though they had walked the world like blind men for a year and a day, and were seeing it plainly again now for the first time there on the rocky ledge.

First they looked at each other in a maze, and then they knew at once what a terrible wrong they had done their grandfather.

“Brother! kinsman!” each cried to the other, “let us fly and save our grandfather.” And they flew as if they had falcon's wings, home to the clearing.

When they came to the glade the cabin was roofless. Flames were rising like a column from the hut. Only the walls and the door were still standing, and the door was still tightly wedged.

The brothers hurried up, tore out the wedge, rushed into the cabin, and carried out the old man in their arms from amid the flames, which were just going to take hold on his feet.

They carried him out and laid him on the cool green turf, and then they stood beside him and neither dared speak a word.

After a while old Witting opened his eyes, and as he saw them he asked nothing about them. The only question he put was:

“Did you find Quest anywhere in the mountain?”

“No, grandfather,” answered the brothers. “Quest is dead. He was drowned this morning in the well-spring. But, grandfather, forgive us, and we will serve you and wait upon you like slaves.”

As they were speaking thus, old Witting arose and stood upon his feet.

“I see that you are already forgiven, my children,” said he, “since you are standing here alive. But he who was the most upright of you three had to pay with his life for his fault. Come, children, take me to the place where he died.”

Humbly penitent. Careful and Bluster supported their grandfather as they led him to the ledge.

But when they had walked a little while they saw that they had gone astray, and had never been that way before. They told their grandfather; but he just bade them keep on in that path.

So they came to a steep slope, and the road led up the slope right to the crest of the mountain.

“Our grandfather will die,” whispered the brothers, ”with him so feeble and the hillside so steep.”

But old Witting only said: “On, children, on —follow the path.”

So they began to climb up the track, and the old man grew ever more grey and pallid in the face. And on the mountain's crest there was something fair that rustled and crooned and sparkled and shone.

And when they reached the crest, they stood silent and stone still for very wonder and awe.

For before them was neither hill nor dale, nor mountain nor plain, nor anything at all, but only, a great white cloud stretched out before them like a great white sea—a white cloud, and on the white cloud a pink cloud. Upon the pink cloud stood a glass mountain, and on the glass mountain a golden castle with wide steps leading up to the gates.

That was the Golden Castle of All-Rosy. A soft light streamed from the Castle—some of it from the pink cloud, some from the glass mountain, and some from the pure gold walls; but most of all from the windows of the Castle itself. For there sit the guests of All-Rosy, drinking from golden goblets health and welcome to each new-comer.

But All-Rosy does not enjoy the company of such as harbour any guilt in their souls, nor will he let them into his Castle. Wherefore it is a noble and chosen company that is assembled in his courts, and from them streams the light through the windows.

Upon the ridge stood old Witting with his grandsons, all speechless as they gazed at the marvel. They looked—and of a sudden they saw someone sitting on the steps that led to the Castle. His face was hidden in his hands and he wept.

The old man looked and knew him—knew him for Quest.

The old man's soul was shaken within him. He roused himself and called out across the cloud:

“What ails you, my child?”

“I am here, grandfather,” answered Quest. “A great light lifted me up out of the well-spring and brought me here. So far have I come; but they won't let me into the Castle, because I have sinned against you.”

Tears ran down the old man's cheeks. His hands and heart went out to caress his dear child, to comfort him, to help him, to set his darling free.

Careful and Bluster looked at their grandfather, but his face was altogether changed. It was ashen, it was haggard, and not at all like the face of a living man.

“The old man will die of these terrors,” whispered the brothers to each other.

But the old man drew himself up to his full height, and already he was moving away from them, when he looked back once more and said:

“Go home, children, back to the glade, since you are forgiven. Live and enjoy in all righteousness what shall fall to your part. But I go to help him to whom has been given the best part at the greatest cost.”

Old Witting's voice was quite faint, but he stood before them upright as a dart.

Bluster and Careful looked at one another. Had their grandfather gone crazy, that he thought of walking across the clouds when he had no breath even for speech?

But already the old man had left them. He left them, went on and stepped out upon the cloud as though it were a meadow. And as he stepped out he went forward. On he walked, the old man, and his feet carried him as though he were a feather, and his cloak fluttered in the wind as if it were a cloud upon that cloud. Thus he came to the pink cloud, and to the glass mountain, and to the broad steps. He flew up the steps to his grandson. Oh the joy of it, when the old man clasped his grandson! He hugged him and he held him close as if he would never let him go. And Careful and Bluster heard it all. Across the cloud they could hear the old man and his grandchild weeping in each other's arms for pure joy!

Then the old man took Quest by the hand and led him up to the Castle gates. With his left hand he led his grandson, and with his right he knocked at the gate.

And lo, a wonder! At once the great gates flew open, all the splendour of the Castle was thrown open, and the company within, the noble guests, welcomed grandfather Witting and grandson Quest upon the threshold.

They welcomed them, held out their hands to them, and led them in.

Careful and Bluster just saw them pass by the window, and saw where they were placed at the table. The first place of all was given to old Witting, and beside him sat Quest, where All-Rosy, the golden youth, drinks welcome to his guests from a goblet of gold.

A great fear fell upon Bluster and Careful when they were left alone with these awesome sights.

“Come away, brother, to our clearing,” whispered Careful; and they turned and went. Bewildered by many marvels, they got back to their clearing, and never again could they find either the path or the slope that led to the mountain’s crest.

VII

Thus it was and thus it befell.

Careful and Bluster went on living in the glade. They lived long as valiant men and true, and brought up goodly families, sons and grandsons. All good parts went down from father to son, and, of course, also the sacred fire, which was fed with a fresh log every day so that it might never go out.

So, you see, Rampogusto was right in being afraid of Quest, because if Quest had not died in his search for truth those goblins would never have left Careful and Bluster, and in the glade there would have been neither righteous men nor sacred fire.

But so everything fell out. To the great shame and discomfiture of Rampogusto and all his crew.

When those two goblins dragged Quest's sheepskin before Rampogusto, and inside it the third goblin, who was still yammering and carrying on like one demented, Rampogusto flew into a furious rage, for he knew that all three youths had escaped him. In his great wrath he gave orders that all three goblins should have their horns cropped close, and so run about for everyone to make fun of!

But the worst of Rampogusto's discomfiture was this: Every day the sacred smoke gets into his throat and makes him cough most horribly. Moreover, he never dare venture out into the woods for fear of meeting some one of the valiant people.

So Rampogusto got nothing out of it but Quest's cast-off sheep-skin; and I'm sure he is welcome to that, for Quest doesn't want a sheep-skin coat anyhow in All-Rosy's Golden Halls.